Mark Jacobs is an Earth Changer.

The Managing Director of SEED Madagascar, the UK charity formerly known as Azafady, talks ecology, poverty, ethics and evolution at the heart of sustainable development.

Places

I was born near the Wembley stadium and schooled in Hammersmith, West London, where there was little to suggest a connection with nature. Thankfully in the UK, we had David Attenborough (my personal God!) on TV with the programme ‘Life on Earth’. ‘A’ Levels [qualifications aged 18] in Economics, Biology and Geography led me to an undergraduate degree in Biology Psychology in Manchester and a study particularly looking at the feeding behaviour of deer – and basically watching their every move! Sounds boring but I loved it. So I followed it up with an MSc in Behavioural Ecology, a mix of ecology and economics, like the sociology of animals, which happily involved me travelling to Ecuador, and a dissertation study on parrots in the southern cloud forests of the Andes. I wasn’t really very interested in the degree per se, more in the learning about the natural world and I was bitten by the bug!

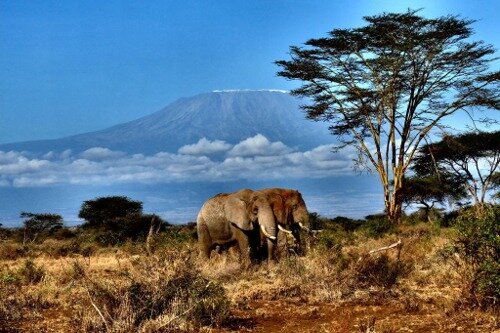

So from Ecuador, I left academia and started working in an art gallery in Manchester for a few years, which I used as a platform for my conservation interests, so it was there I started to plan my independent expedition. But the art gallery owner liked and supported what I was doing and the shop itself was an interesting addition to my life: It sold native American art and brought over native American artists to raise awareness about indigenous cultures and their history of misrepresentation in Western society. So it was a great place not only to raise awareness about issues but also to raise funds for my next expedition, which I had originally planned to be on a reserve in Kenya, building a database on elephants and their behaviour. As it happens, the Kenya politics at the time meant that fell through but someone with whom I was planning happened to know someone in Madagascar - a place, as a biologist, you just want to go to. And so in 1998-9, selling t-shirts in an art gallery in Manchester got me to Madagascar.

The expedition grew bigger and bigger, working with a multi-disciplinary team just outside Fort Dauphin on the south east coast, so I contacted the existing charity then called Azafady (set up in 1994) to support their projects and ended up staying in their office and digs, falling in love with the place and the organisation. At the time, there was just a couple of local staff, plus the original founder and a couple of fundraisers in the UK. They used to generate their money through sponsorship for a balloon race with donated prizes! Their projects were very limited at the time, and there was very little in the way of conservation – the majority of their projects focussed on building and supporting local schools.

And so, having fallen in love with the place and people, I was happily enlisted to boost the environmental side of the organisation, setting up ‘Project Lokaro’, a study looking at one particular forest fragment. And things grew organically from there - around 2002, the charity needed more on-the-ground development so the original founder moved to Madagascar and I took on the London-based role of Managing Director with the aim of building the funding base, working on organisational development and bringing much more attention to the international face of the charity.

Azafady’s founder left the organisation around 2009, and we started a restructuring process in order to support the local Malagasy team's skills to develop greater independence and leadership. Lisa Bass, the newly appointed Director of Programmes and Operations was key in empowering and building the structure of the NGO. And reasonably quickly we started to get larger grants, greater respect and and were able to develop as an organisation to where we are today.

Madagascar wasn’t hugely dissimilar then to how it is now. When I was first there, everyone was poor, apart from a few diplomats. What’s changed now is that some people have started to make money, there is now a growing middle class in Madagascar, but the general grinding poverty is, if anything, worse. Corruption seems to have gone full circle: When I was first involved in Madagascar, it was a difficult place to do anything because you had to pay everyone at each turn. It got better for a period and it’s now got worse again and unfortunately that acts as a barrier to both development and tourism, although it’s entirely non-aggressive. It’s probably the safest place I’ve ever been to. Without doubt, I feel more at risk walking around north London than I do Fort Dauphin. But the successive poor governments haven’t yet addressed the serious issues of poverty that keep the majority of the population in a cycle of deprivation.

In recent years, Fort Dauphin has seen more money coming in due to the [Rio Tinto] mine, which has offered jobs and improved the roads and made the town at least superficially cleaner. But this has increased certain risks as well – lack of sexual education and access to contraception is a major problem, and any influx of people coming in to the area, away from their families and with disposable income, is generally considered to increase prostitution and the risk associated diseases that go with that. This is something we address in our varioussexual health projects with communities and schools which aim to raise awareness and increase education of the issues via very simple messages so people can be empowered to be informed and make their own decisions.

“The people in Madagascar are among the most dynamic, life-loving, and respectful people I’ve had the pleasure of meeting, and like most people in the world they’re more than capable of making their own decisions and directing their own lives for the better; all we try to do is offer them the skills and support they need in order to do that.”

Purpose

The central ethos of SEED Madagascar has always been to help the poorest communities in south east Madagascar tackle extreme poverty and preserve one of the planet's most unique and endangered environments, working towards health and well-beings, sustainable livelihoods and effective management of natural resources. However, organisationally we are quite different now from how we started out, and so how we put that ethos into practice has evolved over the years.

"87p of every £1 of our expenditure is spent directly on projects."

Compared with how we started out life back in 1998, the UK charity structure is completely different, the name is different, and the hierarchy or organisational structure is different, it’s much more of a democracy. The projects we’re running have also evolved: We’re now much more geared to building capacities and connections of communities as opposed to classic development ‘projects’ (although they are still a big part of what we do). In terms of work capacity, reach and impact, we’re probably 2 or 3 times the size we were, meaning we can put applications in for funding from huge multi-lateral organisations like the Indian Ocean Commission , and the EU (until now at least) and have a good chance of being awarded.

The Madagascar NGO team has gone from 2 people when I was first involved to around 50 people, and the UK team in Madagascar has gone from 2 people to around 20 people, whilst the size of the London office has remained pretty much the same growing from just 2 to 3 staff – we are very lean, to focus on maximum impact on the ground in Madagascar. Our trustees have grown and developed with us and are an active board of empowered and informed people who aren’t afraid to challenge as well as support us. So amazingly with all this growth and development there’s not been any explosion of costs – yet we deliver a lot, lot more.

That said, one of the bigger challenges throughout our history has been surviving financially. The next biggest, and very much related, challenge is getting appropriate and able team members, because part of our philosophy is doing the most with the least and being incredibly efficient. So the thing that suffers is staff retention - we can lose very good people, especially in the face of larger charities with big budgets.

But at the same time, one of our biggest successes has been our ability to maintain the organisation’s ethos throughout its growth and evolution, whilst managing to keep the ethos. Being an organisation which can cope with an audit for a multi-million pound grant at the same time as being an organisation where every single person can go and speak to the managing director at any point and be leant a sympathetic ear is a rarity. I think that we are strong at both ends of that scale.

One of the most exciting areas we’re developing at the moment is PHE – the Population Health Environment network, through which we’re running a pilot at the moment funded with Comic Relief which looks at how we can use existing environmental networks to spread messages about population and health. For example, we’ve recently helped to set up the Riaky Committee a group of fairly traditional -male lobster fishermen who risk their lives for their livelihoods every day, but not a classic group of people to whom you would usually talk about family planning. We’re looking to start utilising networks like that, to use untraditional methods and directions to build understanding, because of course the fishermen who are having to work harder, provide more and risk more for every extra child, who needs to be fed, so it’s a message which could very easily be heard and actually be more effective.

So I think the combining of projects is what is happening for us in the future, the building of longer term, larger scale, harder hitting projects – it’s an evolution which has been already been happening for many years and I expect us to take more steps towards in the coming years.

In terms of reporting, every partner organisation partner has slightly different criteria and requirements, for example some will require a short video, some will require a full 50 page report at regular intervals with a copy of every receipt of every penny spent, and there’s everything in between.

One consistent thing we are strong on is project Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL): Understanding whether a project has succeeded and fulfilled its aims by having clear, measureable outcomes and then learning more for the next time because often projects are repeated. For example, when we build a school, surrounding villages say ‘we really need a school as well’ and so we’re in a constant process of refining and improving, ensuring we’re learning from the past whilst also retaining the flexibility to ensure we look anew at every circumstance and context, rather than trying to impose what’s been developed before.

And of course this is only made possible by connection and longevity with the communities with whom we’re working. I think it’s this constant presence that sets us apart from other organisations. Many larger organisations spread their resources very thinly, going where the funding is and not necessarily following up, whereas we stay engaged and accountable to a community for many, many years. Often our staff are from the very communities we’re working with, and we often work with the same community on lots of different projects over time, for example sanitation, livelihoods, tree planting, we may have built their school… and that constant connection strengthens every element within it and is a much, much stronger way of delivering than arriving one day with no connection, building something and leaving.

With its recent restructure and rebranding, SEED Madagascar UK now works with multiple different local organisations to build capacity in Madagascar – including Azafady NGO, our original and main partner. So we are seeing much more collaborative work amongst organisations for the benefit of the communities.

We need to continually be ingrained with the communities and we need to continue to feel like family with our staff, whether they are Malagasy or British, and that friendly, inclusive feeling is something which has remained with us throughout our history and which I’m sure will continue to thrive as we continue to grow.

It’s amazing looking back on how far we’ve come, and how much we’ve managed to hold on to our original ethos - to focus on the most poor and most disempowered and to provide support not only to those greatly in need but to those who are helping those greatly in need, and to never get to the stage where we become impersonal.

At the end of the day we measure our success on the well-being of the Malagasy people: Their health, their education, their workload, their ability to raise their families and their ability to survive alongside the last remaining stands of littoral forest in south-east Madagascar, upon which they depend.

How You Can Be an Earth Changer:

Join SEED Madagascar to help:

- Short term biodiversity research and community conservation

- Short term construction (2-3 weeks)

- Construction and community work (5-10 weeks or as an internship)

- Teach English (2 weeks – 1 year)

- Or Donate: Personal or organisational grants and fundraising